ON the Beat | Croz Talk

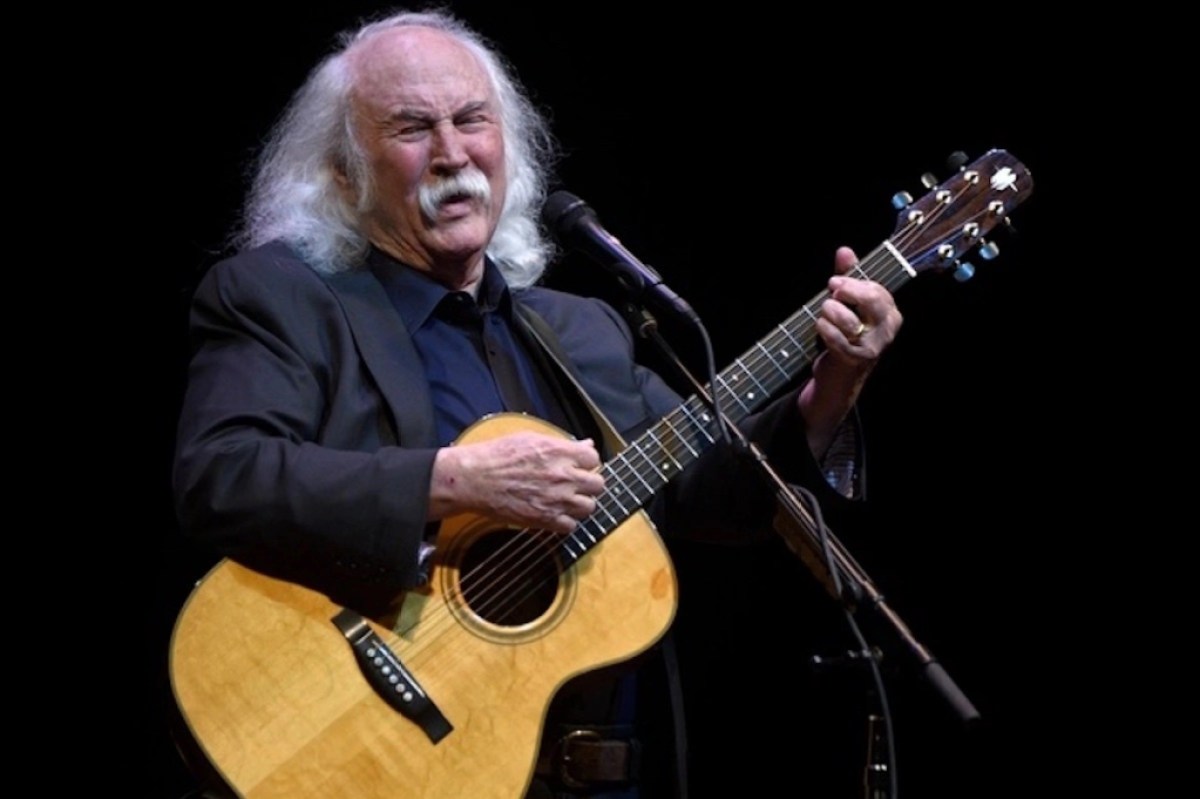

Local-global legend David Crosby’s Passing Triggers an Outpouring of Emotions, Memories and the Blend Thereof

Thinking of a long, rich life in terms of bookends, David Crosby’s discography in solo mode kicked off with his masterful 1971 debut If I Could Only Remember My Name with “Music Is Love,” on which an all-star guest list joins in on the hypnotic refrain “Everybody’s saying that music is love / Everybody’s saying it’s love.” The sentiment is looped into a mantra worth building a life around.

Fast-forward 50 years, and Crosby’s final album, 2021’s For Free (with a light-spirited cover portrait by his pal Joan Baez) closes, prophetically, with the poignant “I Won’t Stay for Long.”

Between those two songs came a fast, furious, sensitive, and fraught life in music. The saga weaves in and out of Crosby, Stills & Nash, work with Nash, reunions with members of The Byrds and with his gifted musician son James Raymond, and a return to his hometown of Santa Barbara for the last few decades (Santa Ynez, to be precise), with his wife, Jan, and son Django in tow.

His passing last week at 81 came as a semi-surprise, partly given the assumption that his illicitly medicated and mischievous early life would lead to an earlier demise, but also because he attained a mystical status. It seemed there would always be a David Crosby in the world. Now, there just remains the legacy, the archives and the deep influences he imparted on other musicians.

He was a guy we kept running into via cameos on local stages. He was also a guy around town, often seen at his cherished eatery La Super-Rica, like the time I saw him run into old friend and La Super-Rica acolyte, Montecitan jazz legend Charles Lloyd. Croz: “What are you up to, Charles?” “Oh man, just working on my tone. Working on my tone.”

In a way, Crosby himself kept “working on his tone” to the very end.Surprisingly, the fruitful and final chapter of Crosby’s solo career began less than a decade ago, when he broke the impasse of not having gone solo (on record) for 20 years. In 2014, he debuted his sorta-eponymously titled Croz with a memorable concert in the hometown haven of the Lobero, confessing that he felt “terrified,” a sign of being on the brink of new creative life.

Connecting with the indie-fueled jazz-pop sensation Snarky Puppy, he since played the Lobero in 2018 after the release of Lighthouse (on the Snarky label GroundUP), and with a band including the inspired jazz-infused folk-pop artist Becca Stevens, also linked to the Puppy machinery. He had earlier sat in at her SOhO show. After the show, I expressed my deep admiration for her work and artistic voice. Crosby, in earshot, piped in, “She’s great!” He was a cheerleader for those he admired, young and old.

Over the years, I connected with Crosby for interviews, leading up to various shows and causes in town. He was alternately expansive, generous, curt and um, snarky — living up and down to his reputation. He could be a boor, but rarely a bore. What follows is selective sampling of excerpts from our conversations, over a nearly 30-year period.

Interview in 1988, before Crosby played a benefit, and shortly after being released from a Texas jail on drug charges, a low point in his life which he has said “saved my life.” He would be moving back to Santa Barbara County a few years later.

Crosby: “[The benefit show] is for the Crane School scholarship fund. I went to Crane and it’s an excellent school. I love it dearly. My daughter goes there. I’m trying to guarantee that their scholarship program is able to make it possible for kids who are bright enough but don’t have the money to be able to go to an excellent school. If a kid is bright enough and willing to work hard enough to excel scholastically, I want the best of them to be able to get access to that level of teaching and information. It matters to me. I hate to see good education be an elitist property of the rich.

“It is a good cause. If there’s any plain, for-sure thing you can do benefits for, it’s kids. Can’t lose on that one.”

Regarding his wry comment that he was kicked out of all the local schools during his schooling years in Santa Barbara: “Well, I wasn’t kicked out of all of them, but I went to most of them. I went to Crane, and to Cate, to Laguna Blanca, to Carpinteria High and Santa Barbara High and to City College. I was raised there from about 5th grade through the first couple of years of college. I’m going to move back there next year. I’m also going to put my boat there. I love it there.”

On the brief resurgence at the time of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young in that period: “It has been a wonderful resurgence, I can tell you that. It’s been a great thing for me, because of my fresh state of mind. I have a lot of new songs and stuff and so I go out and play them all. It’s been particularly good for me because there’s an awful lot of people who are glad that I’m alive and are giving me a lot of support, love, and acceptance.

“We don’t always agree about things; there’s a lot of dissent and a lot of compromise. I think that’s very healthy; that’s one of the reasons it works as well as it does. We also write very differently, which gives us a broad palette of music to paint the music from.”

On the importance of collaboration: “If you cross-pollinate your idea streams … you get all kinds of fresh stuff. If you live in an ivory tower and only do your own thing, that’s kind of like masturbation. I don’t see it. I know that with some of the biggest, most loudly touted talents of our time — Prince and people like that — that’s what they do. But I love learning from other people, singing and writing with other people. I’m writing with a lot of people now. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

“I don’t listen to a great deal of pop music. Some, but only a few. I listen to jazz and classical music a lot. Bach. Also Vaughan Williams, Copland, Beethoven, Sibelius, Mozart … a bunch of people. I particularly like Stravinsky. Béla Bartók is a little strange for me some of the time; it’s like Hindemith or Mahler. I can find places that I think are musical, but I’m more happy with Vaughan Williams’s Theme for Thomas Tallis or, to pick a more egregious example, Copland’s Appalachian Spring.

“I’m picking things that are so well-known that it’s almost in bad taste to like them. ‘Oh, that’s not hip.’ I love really melodic stuff, man. I love harmony and counterpoint. I love musicality. I’m not in it for shock effect. I’ve always been very eclectic. I like a wide range of stuff. I like Ricky Skaggs and James Taylor and Peter Gabriel and Joni Mitchell … Wait ’til you hear Joni Mitchell’s new album. It will just knock your sock off.

“I love all kinds of strange stuff, man. One of my favorite records of all time is one called The Music of Bulgaria, by the National Folk Ensemble and Choir of Bulgaria. It is just the best singing I have ever heard. They make the Beach Boys sound loose. It’s just a bunch of little fat Bulgarian housewives and it’s totally beyond belief.”

Interview in 1992, before Crosby played solo at the Lobero.

I understand that your boat is in Santa Barbara now. Yeah. It has been for a year or so now.

This boat, the Mayan, was the inspiration for “Wooden Ships,” wasn’t it? Yeah. Well, at least “Wooden Ships” was written on it. That song is more like a science fiction epic than about a specific sailboat, but we did write it on that boat. I’ve written a number of songs on that boat.

I always wondered about the origin of “Déjà Vu.” It’s the usual “I feel like I’ve been here before” thing. It came on me very strongly a number of times. There’s no way to prove it. Nobody knows, but there are several things in my life that I felt I might have done before, because I already knew how to do them when I encountered them.

I started singing harmony when I was 6 years old, which doesn’t make a hell of a lot of sense. And then, with sailing, I sort of knew how to make the boat go and knew why the wind did what it did, and how to tack the boat, to go upwind and downwind, from pretty much the first time I saw a sailboat. It was as if I had done it before.

That kind of thing… Now who knows? When I started having these feelings, I was fairly high at least some of the time. [Laughs.] So it all could have been part of my imagination, but that is part of the song, anyway.

That’s a wonderful tune. It’s weird in terms of its structure and that kind of tumbling, looping melody. It’s hardly a typical pop song. I confess, with some secret glee, that I have always been the one who wrote the weird stuff. But I like that. I’m perfectly comfortable being cast in that role.

The oddball? Yeah. No problem.

Were there similarly left field tunes of yours that never made it onto albums, for whatever reason?

Yeah, and there were a lot that did, too. I was strange long before that. Did you ever listen to the thing I stuck onto a Byrds album called “Mind Garden”? It’s early evidence of pre-terminal dementia. [Slips into a Mr. Rogers–like voice.] “You can tell he’s starting to go left right there. You can see it plain as day that he’s not a normal child. He’s gone wrong.”

I’m pretty comfortable with that. Other stuff that I did: On the end of my first solo album, there’s a thing called “I’d Swear That There’s Somebody Here.” That’s certainly out fairly distant in left field. And also the beginning to Wind on the Water, “Critical Mass” — although it’s much more classically oriented — is still not normal pop fare. Neither was “Dancer,” from the Whistling Down the Wire record. On that first solo record, there were several vocal-with-no-words kind of stuff — “Tamalpais High,” and “Song With No Words,” that kind of thing.

I really love pushing the envelope when I can. I’m not some kind of raving genius who can do it all the time. I wish I were. But to the extent that I can, I love to do it. I love it when I run into a Michael Hedges. Earlier on, I never really listened to pop music. For instance, I never listened to Elvis. I was listening to Dave Brubeck, Chet Baker, and Gerry Mulligan.

You got into music via your brother, didn’t you? My brother did teach me an awful lot about it. He was a jazz guy. He turned me onto that stuff at about that point — the Shelly Manne, Chet Baker, Brubeck era. That took me away, and then it’s not very far away from there to Roland Kirk and Cannonball Adderley and then… [Hums the ominous first four notes of Beethoven’s 5th] John Coltrane. Particularly, McCoy Tyner affected my sense of chords a great deal.

It’s not that I didn’t listen to any pop music. I did. I loved the Everly Brothers. But I really was further afield. Also, equivalently, I listened to a tremendous amount of classical music.

My parents — my mother, in particular — loved classical music and played it in our house since I can remember being awake. So that all percolated in there.

But when you first started playing, were you a “folkie”? Yeah — coffee houses in Santa Barbara, and then coffee houses all over the country for a couple of years. I was all over — San Francisco, Chicago, Miami — until I wound up in L.A. and started the Byrds with McGuinn.

So there was a point when you made the conscious decision to pursue the direction of folk music, as opposed to jazz? Yeah, I couldn’t play jazz, asshole. [Laughs.] There was nothing difficult about that decision. And also, I had been turned onto folk music at the same very early time — when LPs were 10 inches. I was turned on to Josh White and the Weavers and Odetta and stuff like that, by my mother, again. That stood me in good stead.

Do you remember some of the local clubs back then? The one I remember the most was the Noctambulist, which was, oddly enough, right next door to the Lobero Theater, in that little alleyway. I washed dishes, for which they would let me get up and sing with a guy named Tony Townsend, who played there. He was a guitar player, singer-folkie guy. He was a very competent guitar player. He would let me sing harmony with him. That was my initial thing. I was still in high school at the time.

So is there a kind of nostalgic sense of coming full circle with this upcoming concert at the Lobero?

Yeah, there is. There was a repertory group in Santa Barbara in a little repertory theater just off of State Street that’s no longer there. It got torn down many years ago. I was in it for two or three years during high school. I loved it dearly. We put on a Santa Barbara Follies kind of show, a spoof of everybody in town that some jerk had written. It was terrible, but we did it at the Lobero. We did a couple of different things at the Lobero and I loved it.

If I think about your solo albums, the titles seem significant. They try to be significant, and usually they’re too long.

If I Could Only Remember My Name was such a perfect name for that album and its aura. That had to do with déjà vu, and the idea of feeling that I had been here before. That’s where that title actually came from — the feeling of “Jesus, I wish I could remember who the fuck I was.” Everybody thinks it’s about being stoned, but it’s not. It’s other lifetime stuff.

That was a very strange album when it came out, but also very influential on people like me. I was an impressionable teenager when that came out, and it helped open my ears and led me into other kinds of music. How does it stand up for you? Do you listen to it? I love it, because I did exactly what I wanted and it came out being truly representative of the kind of music I was playing then. And it really didn’t sound like, and still doesn’t sound like, anybody else. I can’t think of any of the songs I didn’t like.

You’re a collaborative personality. Yeah. I really love it. I tell you, I had a key experience when I was very young. My mom took me to hear a symphony orchestra and we were sitting right up front where I could see them. It was outdoors. It was a little local symphony orchestra. We were sitting on grass and folding chairs.

I remember being bowled over by the sound, just emotionally being pinned to the wall. It was big and exquisitely beautiful. I was about 4 years old … It completely took me by storm. It was a searingly good experience, okay? At the same time, some little part of my brain kept noticing all the little elbows going up and down together. All the little tootle-y tootle-ies going together with their hands. Something connected up in there, that when you did stuff together, it made that kind of magic.

So I was a dyed-in-the-wool band player, harmony-singer guy before I even got to bands or harmony. I was already totally set up for that emotionally. It is, I confess it readily, my chief joy. I think that the whole is better than the sum of the parts. The multiplication and magic that takes place between players when they are inspiring and pushing each other above their own heads — there’s something that happens. It’s bigger than a human being can get.

When the music gets to a certain force level, a certain level of magic, it gets so good that egos tend to be subsumed, to be diminished. Something greater is allowed to pop into existence

between the musicians. That is the chief magic of my life. I dearly love it.

And then, to be able to cast it out over the stage and to the audience and to engage that magic is wonderful. I really love it.

Interview in 2016, before he played at The Granada Theatre.

You are about to play at The Granada Theatre. Have you played there before? No, that’s the one place I haven’t played, so it’s good that I’m doing it. I’ve played the Lobero since I was about 17 years old. I can’t even count how many times I’ve played the Bowl. Since they rebuilt the Granada, it’s a very beautiful room. I’m really looking forward to it.

You have talked about playing in a tiny and long-since-defunct folk club next to the Lobero. I can’t remember the name of it off-hand… I can’t even remember it myself. Oh, it was called the Noctambulist, which means “night walker.”

Is there a special emotional baggage or flavoring when you play in your hometown, compared to other places? Yeah, somewhat. Some of it is “hometown boy makes good,” and some of it is nostalgic. Plus, the Santa Barbara audiences are just really great. It has always been a joy, every time. And you never know who’s gonna show up. I’ve got a lot of friends in town, and a lot of the usual suspects will show up.

To get the general arc of the story straight, you basically grew up in Santa Barbara, went off to Greenwich Village and various corners of the world and came back, somewhat prodigal-son-like, a few decades ago, and have been in Santa Ynez ever since. Is that about right? Yeah. I went off on the road as a kid, as a folk singer, and came back to Los Angeles and started The Byrds, spent a couple of years with The Byrds. Then I started Crosby, Stills & Nash and spent a couple of years in that, then a couple of years as Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

After a long time of doing those two groups, in the last couple of years, I’ve started doing solo stuff again, because it’s so rewarding. I get to sing a whole bunch more songs, and songs I don’t otherwise get to sing. In the group, you wind up doing your hits, turn on the smoke machine and the lights and do a show of your hits. Well, that’s fun. It’s fun to rock.

But I really love the words and I love taking people on a little voyage. This kind of thing, doing it solo acoustic, if you are willing to go to the trouble, you can actually do some pretty good work, and that matters to me a great deal.

Thinking of musicians of your generation, you and Joni Mitchell took that jazz connection to heart and found a way to mix jazz ideas into folk, rock, and other directions. It affected both of us. And of course, Joni is the one who turned me onto tunings, which has been really good for me. I’m just a happy guy.

You played at the Lobero and unveiled new material which wound up on your album Croz. That was somewhat daring. Did you recognize it would be that way, for people who maybe wanted to bask in nostalgia? Well, I have no explanation for why I’m in this writing search that I’m in, but I’ve been in it for a bit now. I am thrilled by it. I can’t explain it, but I am deeply grateful for it. I’m trying to pay attention and work at it, do the best work I can possibly do.

I can’t really explain it. I can’t explain why I can sing, even after everything I’ve been through. But if the muse comes, you should be grateful and work at it.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.