Abstract States of Mind, at the Museum of Art

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art Taps its Permanent Collection’s Abstract Art Resources for the Exhibition ‘Going Global: Abstraction at Mid-Century’

Consider it a logical paradox. Going Global: Abstraction at Mid-Century, the new main exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, is an inherently nostalgia-waxing survey about a sweeping, once-radical force in 20th-century art. Abstraction has lost its sting and its sense of mission, and the show, drawn from the museum’s permanent collection, serves as a reminder that yesterday’s revolution can transform, in some ways, into today’s comforting relic.

Progressive energies turn reflective in hindsight. Abstraction, which overturned prevailing art-world truths when Kandinsky and others kick-started the notion in the early 20th century and through successive reinventions via Abstract Expressionism and other movements by mid-century, is by now an accepted part of the cultural landscape. It appears as innocent eye candy on bank and corporate walls and domains where decorative imperatives prevail.

Of course, its potent aesthetic imprint is still vital and infuses contemporary art notions, both “traditional” and hybridized into new forms and elaborations. But what would Kandinsky, Gorky, Pollock, and other abstracting titans think of the fate of the abstract impulse in art?

A modest proposal with an educational overview, Going Global addresses the many side routes and offshoots of the abstract mothership, not to mention contributions from the “global” community (a k a beyond America and Europe).

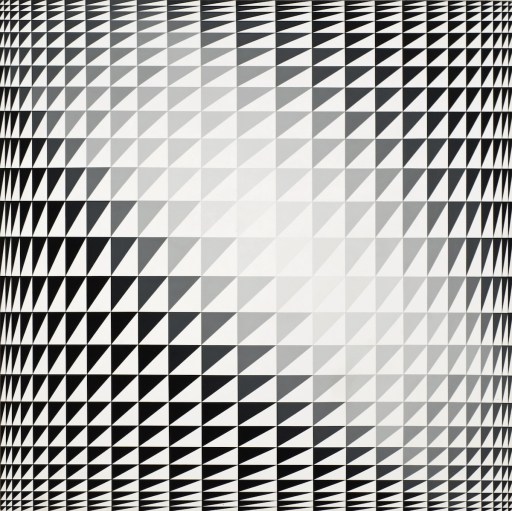

For an immediate indication of the sharp contrasts under the abstract art umbrella, we enter the McCormick Gallery and are amiably confronted by the op-art eyeball buzz cut of Richard Anuszkiewicz’s 1979 “Centered Green.” Turn right and we take in the gestural, seeping color fandango of Ernst Wilhelm Nay’s “Chromatik stark und zart” (“Strong and tender colors”). (Biographical note: Nay, deemed by the Nazis as a “degenerate artist,” was drafted into the German army, where he befriended Kandinsky.)

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

Thicker, darker, and more palpable gestures mark the painting “10 Mai 1961,” by French painter Pierre Soulages, one of the better-known art-world figures represented in the show. Inspired by the cavernous light and atavistic aura of Lascaux and Altamira, Soulages created something mystical in paint here.

A side gallery is devoted to the assigned category of “Signs & Symbols” and features lesser lithographs of famed artists. Lee Krasner (Jackson Pollock’s wife and widow) shows spare and becalmed “action” pieces in varied shades, while Jasper Johns’s “Souvenir I” contrasts a gradated gray expanse with a mugshot-like self-portrait in the lower corner.

Meanwhile, back in the op-art zone, we find the woozy mesmeric optical charm of “Annul” (1965), by Bridget Riley, a star of the genre. Literally shifting perspective, as beholders, is required to fulfill the desired impact and optical trickery of Yaacov Agam’s “New Year, III.” He craftily packs three bright-hued compositions into one, depending on the position of the beholder.

Other artists bring personal underpinnings and guidance mechanisms to their work represented here. Kenzo Okada’s large but soothing “Insistence” insightfully blends the calligraphic impulses from his native Japan with Abstract Expressionist impulses not too dissimilar from, say, Franz Kline. Famed Brit artist Ben Nicholson’s loosely geometric and drawing-like “Topaze” is, the artist claims, a reflection on his foggy seaside family home, turning still lifes into “land-sea-sky-scapes.”

Elsewhere, the distance between carefully curated abstraction and realism becomes a central driving expressive driving force. Of the photographs in the show, the strongest and most relevant is André Kertész’s “Martinique,” in which an image of an ocean-front hotel balcony — with a figure blurred behind frosted glass — is a mysteriously elegant, minimal jewel of a vision.

Possibly my own Best of Show nod, partly for sentimental reasons, goes to Gunther Gerzso’s “Le temps mange la vie/El tiempo se come a la vida” (“Time Devours Life”), from 1961. With its poetically layered group of forms, as if furling fabric pieces in an alternate dimension, the painting triggers real-world and dream-like responses.

From another in-house historical angle, the painting is a beautiful reminder of SBMA’s important one-person exhibition of Gerzso’s art in 2003, through which I and many others “discovered” this too-obscure Mexican artist’s voice and vision.

A single painting, abstract or otherwise, can have the power to fling us back in time and memory, even as time devours life.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.